In October 2025, Lakewood adopted a landmark zoning code that legalizes more compact and affordable housing options citywide. The reform is designed to expand housing supply and diversity, improve affordability, support sustainability goals, and better reflect the demographic shift toward smaller households. With this update, Lakewood is reintroducing starter home options in a city where they have all but disappeared, and setting the gold standard for Colorado communities facing similar challenges.

Why Lakewood needed reform

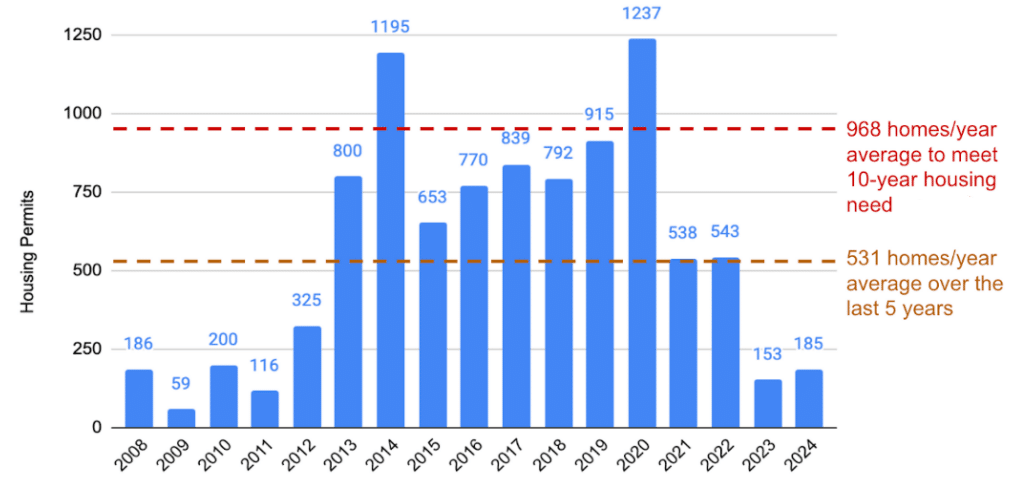

For decades, most of Lakewood’s neighborhoods were zoned exclusively for single detached homes on large lots, leading to predictable consequences. Since 2017, Lakewood’s median home price has increased by more than 50%, rising from $367,000 to $560,000. Over half of renters are housing cost burdened, spending more than 30% of their income on housing. A 2024 Regional Housing Needs Assessment estimates that Lakewood must add almost 1,000 new homes per year to meet current and future demand, double its recent pace.

New housing permits in Lakewood (2008-2024)

Source: HUD building permit database

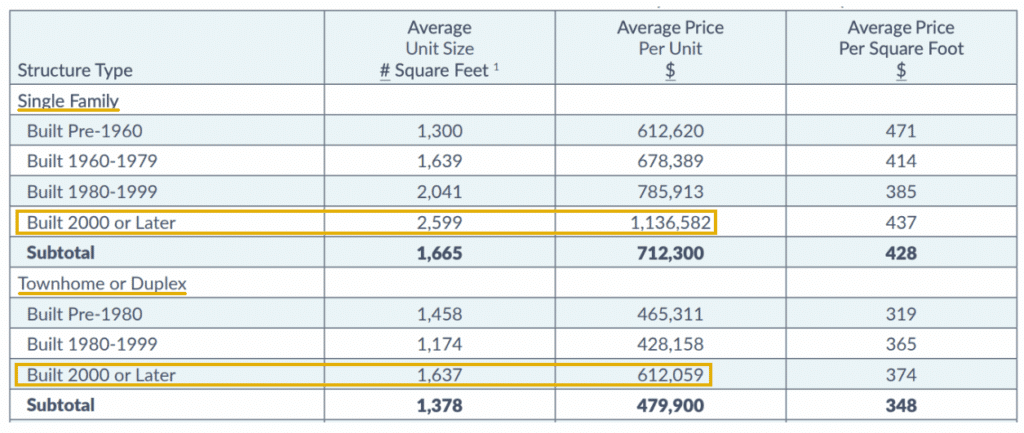

Quantity is one problem, and a lack of diverse housing types is another. New construction has mostly been large detached houses or rental apartments, with very little in between; only 3.4% of Lakewood homes built in the last decade were in 2-4 unit buildings. This narrow range of offerings no longer fits a city where nearly three quarters of households now consist of just one or two people, including seniors living independently and couples who are waiting longer to start families. New detached houses built this century average 2,600 sf, even as smaller formats have proven far less costly. Townhomes and duplexes built in the 21st century sell for $500,000 less than single-unit homes ($600,000 vs $1.1 million), offering more affordable, appropriately scaled options for Lakewood’s growing share of small households.

Lakewood housing characteristics over time

Source: Lakewood Strategic Housing Plan

What changed in Lakewood’s new zoning code

The new code blends a range of best practices in housing policy with priorities specific to Lakewood. The centerpiece of the update is allowing middle housing types such as duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, and cottage clusters on all residential lots. Most of these lots were previously limited to detached single family houses on large parcels. The reform also introduces smaller lots, more flexible parking rules, and new opportunities for neighborhood-scale retail, all while maintaining familiar building forms and height limits. To simplify the code, the nine previous low-form residential zones were collapsed into three: urban, suburban, and rural.

The new zoning code will provide more affordable housing opportunities by:

-

- Legalizing more homes per lot. Beginning in 2027, there will be no maximum number of dwelling units per lot; scale will instead be controlled by building size and design standards. A transitional year in 2026 will allow up to 3 units per structure.

-

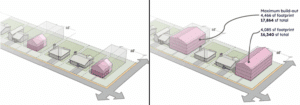

- Modifying building size limits. Above-ground area is capped 4,000 square feet (sf) for one- and two-unit buildings, and 5,000 sf for three or more units. Alongside standard setbacks, the continued 35-ft height limit, and a 50% lot coverage cap, this keeps new developments in scale with existing single-family home neighborhoods. Single-unit “McMansions”, previously allowed to at a scale of 15,000 sf or more on many lots, will no longer be allowed.

-

- Permitting flexible lot sizes. Minimum lot sizes are reduced across the city to 1,500 sf in low-form urban areas, 5,000 in suburban, and 7,000 in rural contexts—offering more efficient land use options for Lakewood’s spacious lots, which average over 9,200 sf. This will allow property owners to subdivide their lots and build multiple smaller and more affordable single-family homes, townhomes, or other middle housing types on each lot if they choose to do so.

-

- Allowing greater parking flexibility. Following state law (HB 24-1304), parking minimums are eliminated for multifamily projects near transit, allowing builders to right-size new parking to the needs of their particular project. In addition, all affordable housing projects are exempt from parking minimums citywide. In low-form residential areas, buildings under 4,000 sf don’t require parking, while buildings above that require one space per additional 1,000 sf.

-

- Encouraging Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs). Lakewood already allowed ADUs (small secondary homes such as backyard cottages or converted garages), though very few have been built. The new code aligns with state law (HB 24-1152) by eliminating some barriers to feasibility like excessive parking requirements, while going further—allowing larger ADUs, up to 1,400sf.

-

- Allowing neighborhood shops. For the first time, small retail spaces, up to 750 sf, are permitted in residential neighborhoods, advancing the city’s goal of creating walkable, complete communities. It is envisioned that communities can be enriched by a wide variety of very small neighborhood-serving enterprises such as coffee and flower shops or yoga studios.

-

- Prioritizing wildlife and parks. Lakewood residents have strongly advocated for protection of parkland and wildlife in recent years. The zoning code addresses this by requiring bird-safe glass in some situations, and by tightening height restrictions for new buildings adjacent to large parks.

Middle housing allowed now contrasted against the oversized houses allowed before

Source: City of Lakewood

Lakewood should expect moderate growth in affordable homeownership opportunities with little impact on demolitions or displacement.

It’s too early to know exactly what Lakewood’s new zoning will yield, but Portland, Oregon offers one of the clearest real-world precedents for this type of reform. In the first three years after a similar reform in 2021, Portland has permitted roughly 1,400 middle housing units and ADUs, selling for $250,000 to $500,000 less than new detached houses (SWEEP wrote about Portland’s reform here). Hardly an overnight transformation, but a modest yet meaningful amount of new homes scattered throughout the city. Key takeaways from Portland’s experience include:

-

- Broad distribution. New homes have been well distributed across wealthier and more vulnerable neighborhoods—a welcome result following concern about concentrated development in lower-income neighborhoods and potential displacement.

-

- No increase in teardowns. Demolitions have not ticked up, though 3 or 4 units are now typically built when a demolition does occur instead of just one large detached home.

-

- More for-sale housing. A majority of new middle housing units are built for ownership rather than rental.

Middle housing comes in many forms

Clockwise from top left: townhomes in Denver; a cottage cluster in Portland; small-lot houses with ADUs in Leadville; a Denver duplex.

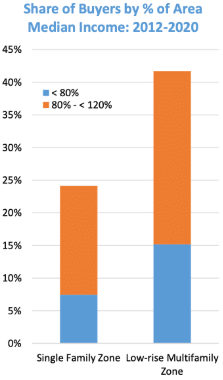

Portland’s results are consistent with the pattern that middle housing is often built as for-sale homes rather than rentals. In Seattle, about two-thirds of newly built townhomes are owner-occupied, compared to roughly 10 percent of units in larger multifamily buildings. Because of their naturally lower cost, these ownership opportunities are within reach for more low- and middle-income families. Buyers earning 120% or less of AMI make up only 24% of homes in single-family zones, compared to 42% in townhome zones. With larger multifamily condo construction stalled due to construction-defect liability issues, and subdivisions on undeveloped natural land being so fiscally and environmentally costly (more on this below), middle housing offers a path forward without these downsides.

Lakewood’s winding path to reform

This update ushers in a new chapter for a city that has developed an anti-growth reputation in recent years, most notably for its 1% annual growth cap, narrowly approved by voters in a 2019 off-cycle ballot initiative. The ensuing freeze in housing production in the face of rising prices led to the election of a pro-housing city council with a mandate to expand housing opportunity and affordability.

The Strategic Housing Plan, adopted in February 2024, documented the shortage, recommended smaller lots and homes, and found strong public support for doing so. It included a public survey finding 50% support and only 33% opposition to allowing middle housing in single-family zones, providing evidence that the community was ready for change.

Following the housing plan was an update to the comprehensive plan, adopted July 2025, establishing goals for a diverse and affordable housing market and a sustainable built environment. The plan explicitly called for diversified housing types and mixed income neighborhoods, walkable communities, modernized parking, and resource-efficient buildings.

With these plans in place, updating the zoning code to legalize middle housing became the natural next step—and perhaps the most viable way to deliver on Lakewood’s housing and sustainability commitments. At the first council hearing on the code, public support outnumbered opposition about 4:1. Following extensive public engagement, the city council approved the final code by a vote of 8-3 in October 2025.

Mere weeks later, all city councilors up for reelection who voted for the zoning code update won at the ballot box with comfortable margins. Councilor Sophia Mayott-Guerrero reflected on the mandate:

“When I ran for office, I knocked on thousands of doors. Most people brought up the importance of affordable housing, walkable neighborhoods, and improved sustainability measures. This zoning rewrite was the largest step we could have taken on all of these issues.”

Housing as a sustainability strategy

Middle housing reduces the environmental footprint of growth. Allowing more homes in existing neighborhoods curbs sprawl, shortens trips, and uses far less land, water, and energy. CDOT finds suburban residents drive twice as many miles as those in more urban areas, underscoring how “smart growth” policies like Lakewood’s can cut transportation emissions by at least 15 percent along the Front Range. Compact and multifamily housing types require significantly less energy to heat and cool; the Colorado Energy Office (CEO) found that smart growth policies can reduce all new housing’s building operations emissions by 31% by 2050. In addition, small multifamily buildings consume 63% less water per household than detached homes. CEO estimates that widespread smart growth in Colorado can shift 30% of new home construction from greenfield development to infill areas where infrastructure already exists.

Lakewood sets the stage for other cities to legalize middle housing.

These combined impacts help explain why Lakewood’s reforms drew support from housing advocates, environmental and business groups, faith leaders, nurses, AARP, affordable and market-rate homebuilders, and residents seeking better housing options. The broad coalition reflects recognition that Lakewood’s approach addresses multiple intersecting challenges that affect the whole community.

Lakewood’s overhaul shows how Colorado communities can confront affordability, climate, and the realities of today’s housing market. By updating its zoning to reflect modern household needs and sustainability goals, Lakewood has provided a practical roadmap for other cities considering similar reforms. As cities like Aurora, Denver, Brighton, Boulder, and others explore middle housing, Lakewood’s experience shows that legalizing smaller homes is both feasible and widely supported. Middle housing is quickly becoming a core component of how growing cities can plan for a more affordable, resilient future.

Note: Citizens have begun organizing a referendum to overturn this reform. As of publication, signatures are being collected and the outcome is uncertain.

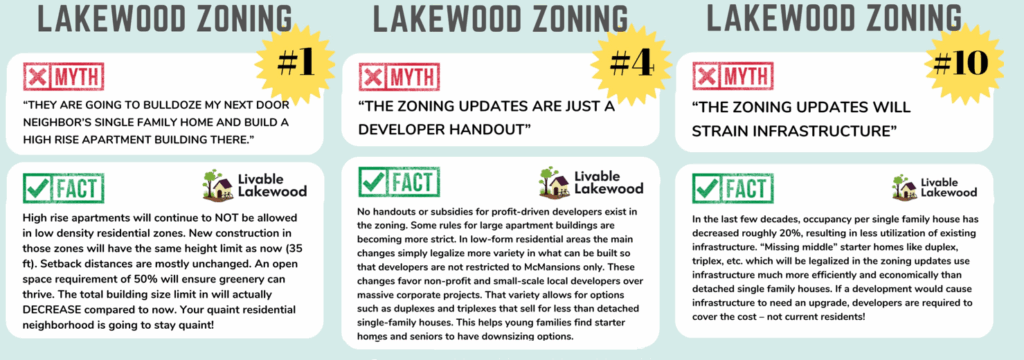

For additional resources on this reform, see the Housing Forward Colorado / Livable Lakewood fact sheet and webinar recording, and Livable Lakewood’s series addressing common misconceptions, three of which are excerpted here: