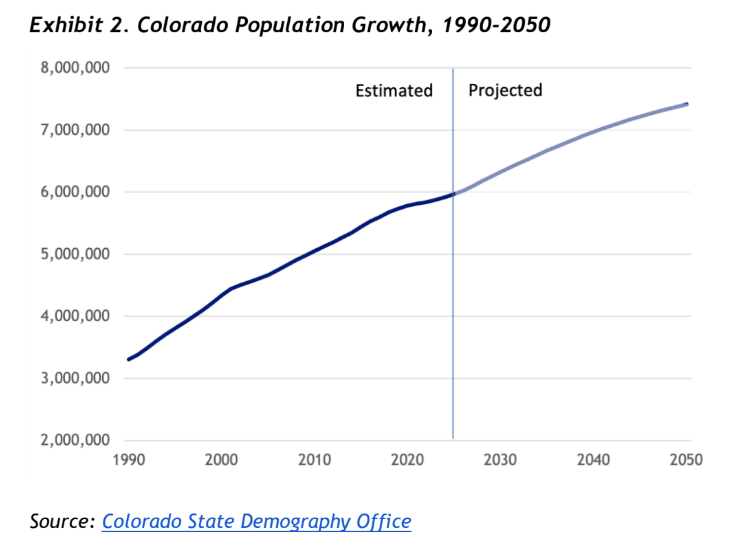

State demographers expect Colorado to add another 1.5 million people by 2050, growing by 30% to a population of more than 7.4 million. With 90% of that growth concentrated along the Front Range, the question before us is not about whether we will grow, but how we grow. Where will everyone live? How can we make sure folks – both existing residents and new – can afford to live here? And how can we grow in a more environmentally and financially-responsible way? How can we grow in a way that protects what we love so much about our special state – our open spaces, scenic vistas, and wildlife – while ensuring our kids aren’t priced out of the communities they grew up in? The state already faces a housing shortage of 106,000 homes. That need will only worsen as Colorado’s population grows, unless we build enough housing to close the current gap and keep up with projected growth. To accomplish this, we must be more strategic about the kinds of housing we choose to build and where we choose to build it.

Those choices have massive impacts on both affordability and sustainability. To put it simply, we can tuck more affordable homes into urban neighborhoods where infrastructure and services already exist – or we can pave natural and agricultural lands to build large and more isolated single-family homes far from city centers. The former is strategic growth (also known as smart growth); the latter is sprawl.

In this blog post, the second in a series about strategic growth in Colorado, we will describe key takeaways from a Statewide Strategic Growth Report recently published by the Colorado Department of Local Affairs (DOLA). Our first blog post in the series focused on a 2024 Colorado Energy Office study about the climate benefits of smart growth. Our next post will explore some of the policies and financing tools that impact Colorado’s growth patterns and what we can do to promote smarter growth.

Colorado’s history of urban sprawl

Colorado has tried and failed to rein in sprawl in the past. For example, in 2000, the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG) coordinated the Mile High Compact, an agreement between participating governments to establish voluntary Urban Growth Boundaries (UGB). Those boundaries identified where new development and public services would be focused, in an effort to direct growth inward and reduce outward sprawl. The boundary did not hold and the UGB area was repeatedly expanded from 700 to 900 square miles in 2007 to 1,308 square miles in 2022, almost doubling in size over a 22-year period. In contrast, the Portland metro area’s UGB has expanded just 14% over the last 44 years despite similar population growth rates to Denver. From 2001-2011, Colorado lost 525 square miles of natural lands to development, second only to California in the American West – and across the state, not just in the Denver Metro area. Clearly, a new approach is needed.

Comparing two land use scenarios: The status quo vs strategic growth

Colorado’s latest effort to examine its growth takes the form of a Strategic Growth Report published by DOLA on Oct. 31, analyzing the numerous benefits of strategic growth policies – and the consequences of sprawl – in the Centennial State.

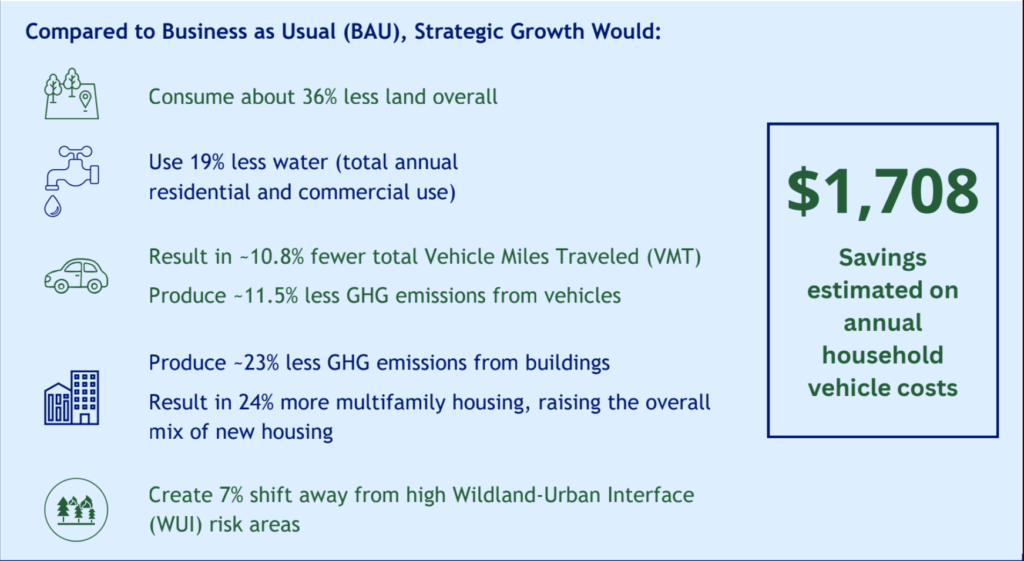

The Strategic Growth Report compares a baseline “business as usual” scenario to a strategic growth scenario. On a high level, the report shows that we should prioritize infill housing in our existing developed areas rather than allowing exurban sprawl – especially when it’s dispersed, “leapfrog” development. The reasons for this are numerous: household costs, transportation impacts, land conservation, infrastructure costs, wildfire risk, greenhouse gas emissions, and more.

Source: Colorado Strategic Growth Report Fact Sheet, DOLA

The five place types

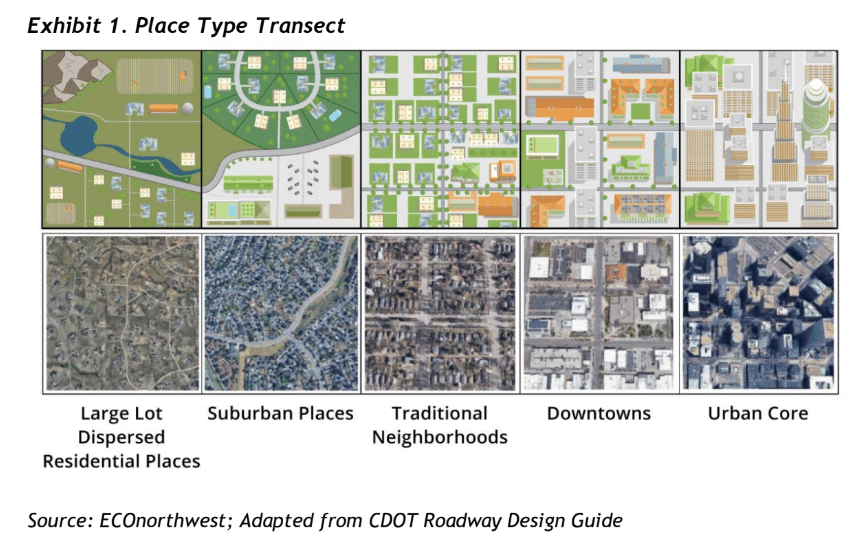

DOLA’s report defines five “place types,” to describe a range of different development patterns:

- Large lot dispersed residential: ~0.26 homes per acre; common in many older and more rural single-family neighborhoods.

- Suburban: ~5 homes per acre; large homes on large lots at the urban edge; common across the Front Range.

- Traditional neighborhoods: ~8 homes per acre; small single-family homes with some duplexes and small apartments in urban areas.

- Downtowns: ~25 homes per acre; mixed-use, walkable areas with apartments and businesses.

- Urban core: ~50 homes per acre; primarily commercial with apartments in taller buildings.

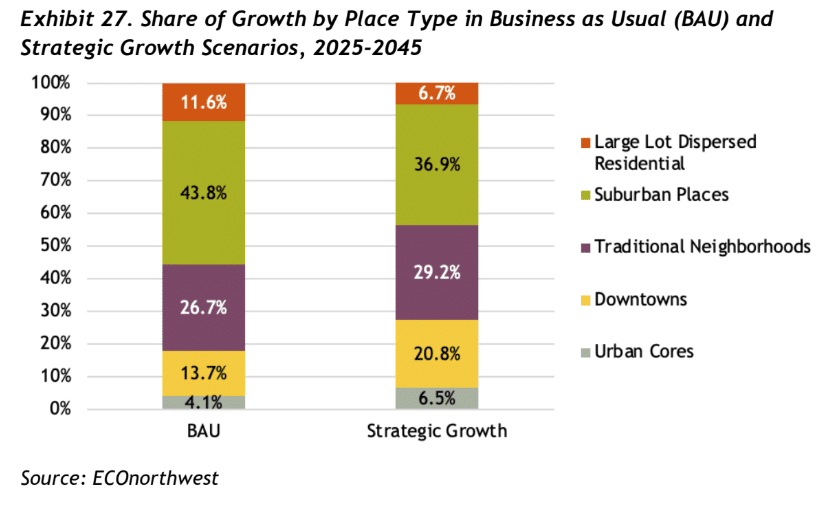

A Strategic Growth (SG) Scenario assumes we shift a significant but reasonable share of projected housing growth from large lot dispersed and suburban place types to traditional and downtown neighborhood place types with a more diverse mix of housing options and better access to existing infrastructure, jobs, and amenities.

Nine ways strategic growth benefits Colorado’s economy and environment

Housing on the urban fringe is often marketed as more affordable than city living, but once we factor in the added costs of car-dependence, metro district taxes, insurance, and larger utility bills, it’s often far less affordable than advertised for the residents living there. Beyond these direct costs, sprawl shifts significant financial burdens onto governments providing roads and emergency services that low-density development doesn’t fully pay for, and further socializes costs across all Coloradans through insurance premiums, utility rates, traffic, pollution, and the loss of land and water. Strategic growth offers a more cost-effective, sustainable, and resilient approach.

1. Saving Coloradans money on housing

In Colorado, the current status quo of widespread single-family zoning has artificially limited housing supply, driving up housing costs across the board. Across nearly 70% of residential land in Colorado, local zoning prohibits any kind of homes except for detached single-unit homes, which tend to be much more expensive than attached and multifamily housing types.

Strategic growth policies encourage more affordable housing types, such as attached and multifamily homes. In Lakewood, for example, “middle housing” types like townhomes and duplexes built this century sell for roughly $500,000 less than single-family homes ($600,000 versus $1.1 million), according to the city’s 2024 Strategic Housing Plan. Updating land use and zoning regulations to allow more housing choice in our cities is essential to expanding supply and bringing down costs for everyone.

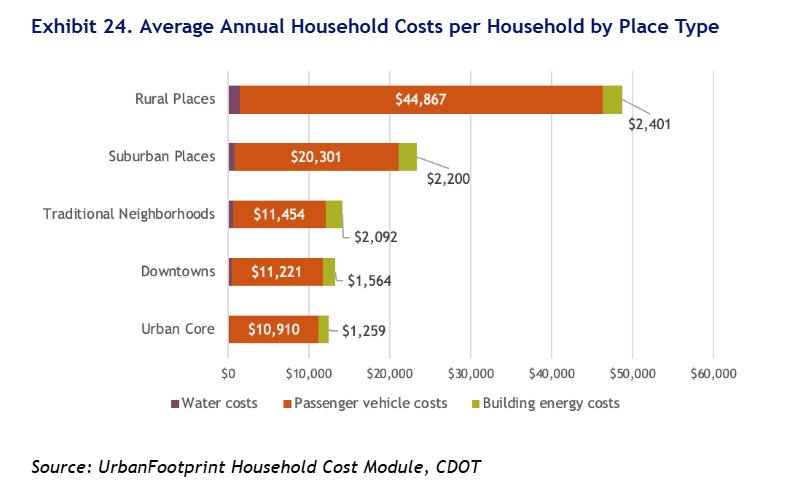

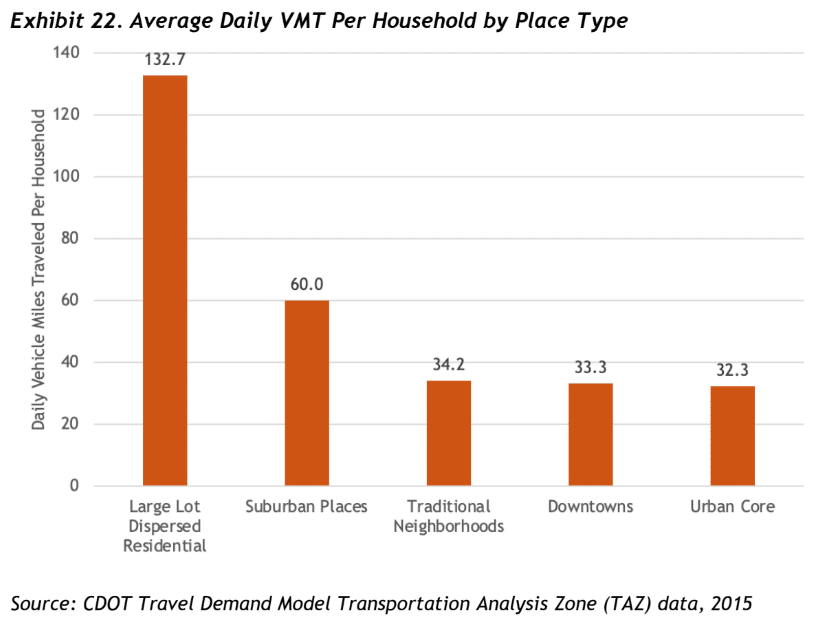

2. Saving Coloradans money on transportation

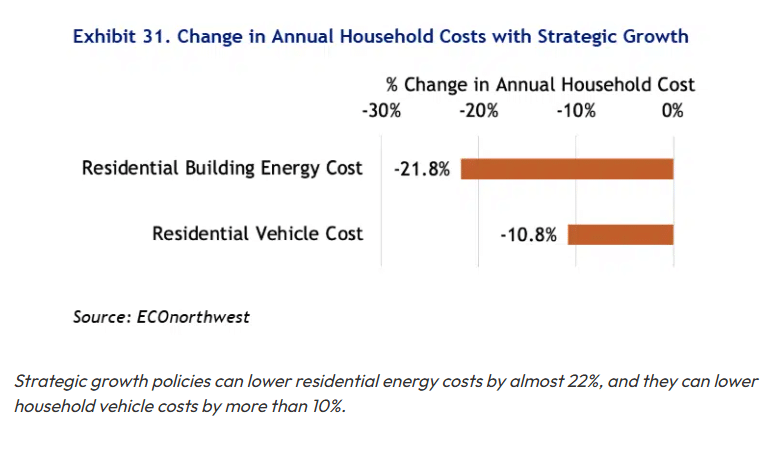

The Strategic Growth Scenario would save Colorado households an average of $1,708 annually in vehicle costs by reducing total driving by 10.8%.

Coloradans living in the suburbs drive twice as much as those living in urban neighborhoods – even traditional neighborhoods where the majority of housing is single-family homes. That results in much higher transportation costs: from purchasing a car or paying off a car loan, to buying fuel, to vehicle maintenance, to insurance (in a state that already has the country’s sixth-highest auto insurance costs, with rates continuing to rise). Transportation is the second largest expense for Colorado households, behind housing. A household that shifts from two cars to one can save over $12,000 annually.

Families living in the suburbs or more dispersed exurban areas spend 2-4 times more money on transportation than those in urban neighborhoods. This is partially because traditional neighborhoods tend to have a better mix of residential and commercial land uses, and enough population to support nearby local businesses, so there are places to walk to while trips by car are shorter. In contrast, suburbs and large-lot residential areas tend to be homogeneous neighborhoods with weaker transportation connectivity and walkability (more cul-de-sacs and less public right-of-way). Even if they have sidewalks, there are very few destinations to walk to in such areas.

3. Saving Coloradans money on energy

The report found that strategic growth policies can lower residential energy costs across Colorado by almost 22%. Smaller homes have lower energy bills – first, because there’s less space to heat and cool, and second, because homes that share walls (and sometimes floors/ceilings) are more energy-efficient (e.g., less heat or air-conditioning escaping from outer walls). This could provide welcome relief for Coloradans facing higher energy bills in the face of rising electricity rates.

4. Saving local residents money on infrastructure

Strategic and compact growth are more cost‑effective because many urban areas already have enough infrastructure capacity to support additional homes, and their higher densities and job concentrations produce the tax base needed to maintain those systems over time. In contrast, sprawling development often requires brand new infrastructure like roads, pipes, and utilities as well as new services like fire stations, schools, libraries, and transit to support far‑flung growth. The lower density development with relatively few jobs does not generate enough tax revenue per acre to cover the full cost of new infrastructure, pushing those costs onto local governments and future residents over the long term.

To finance new sprawl-enabling infrastructure, Colorado developers commonly establish special districts known as Metro Districts. While this arrangement helps cover upfront costs, it can give new homeowners a false sense of affordability. Metro district taxes often phase in one to two years after a home is first occupied, leading to significant and unexpected increases in housing costs. The Denver Post’s article “Colorado metro districts and developers create billions in debt, leaving homeowners with soaring tax bills” described one example where a family living in a new Johnstown community reported their property tax bill rising from about $800 to more than $5,000 in five years, with nearly half going to the development’s Metro District to finance the new infrastructure. The sudden cost increases ultimately led to the family losing their home in foreclosure.

A new master planned community on the eastern edge of Aurora (Source: Google Earth)

5. Saving regional taxpayers money on infrastructure

The impacts of sprawling development are also felt regionally. While exurban subdivisions and their Metro Districts may pay for local roads, they do not address impacts on the broader transportation system. Car-dependent sprawl adds traffic to existing road networks and creates pressure to widen highways in urban areas with the costs ultimately borne by Colorado taxpayers. CDOT recently spent $1.3 billion widening I‑70 through Denver and is now considering at least another $1.6 billion to widen I‑270 and I‑25 to serve future car-dependent development on the urban fringe, diverting limited funds from basic road maintenance and transit.

Similarly, on the utility front, sprawl stretches long, exposed power lines and substations across the Wildland–Urban Interface (WUI), raising both the cost of grid hardening and the risk of catastrophic wildfires across the region. Earlier this year, the Public Utilities Commission approved Xcel Energy’s $1.9 billion Wildfire Mitigation Plan, which is expected to raise residential customer bills by $9 per month to reduce fire risk. The state’s insurance plan of last resort, launched in 2025, is yet another example of the increasing need for public backstops when markets can no longer absorb these risks.

More generally, public services cost more per capita when populations are more dispersed because resources are stretched further over large areas, some of which include wildfire-risk WUI areas. For example, the Parker Fire Protection District estimated that serving 50,000 residents in low-density residential and suburban place types would require eight fire stations, costing a total of $12 million. If the residents lived in more compact neighborhoods, firefighters could serve the same population with four or five stations, costing $6-$7.5 million, a potential savings of 37.5 to 50% for fire stations alone.

Prioritizing smart growth can help alleviate these issues and enable cities to use their limited financial resources more prudently, especially at a time when the state is facing a $850 million budget shortfall. A study of the Denver Metro area found that compact development could reduce infrastructure spending by as much as 80% relative to more dispersed growth, while also protecting farmland, habitat, and forests. Another study estimated that adding 150 square miles of new development, instead of focusing on infill where infrastructure already exists, would cost an additional $7.46 billion in infrastructure, adjusted from the study’s 2009 dollars.

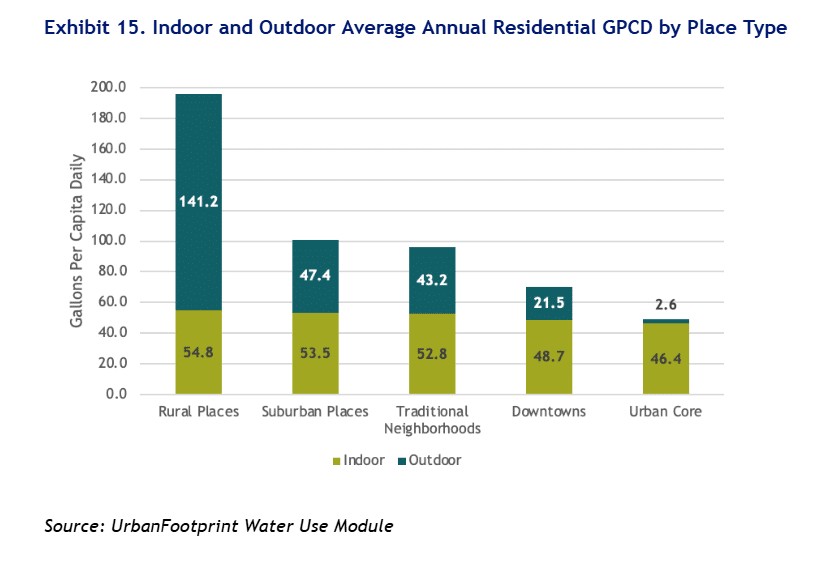

6. Conserving water

If current trends continue, the Colorado Water Conservation Board anticipates a significant water shortage by 2050. Land use patterns play an important role and DOLA’s analysis found that low-density urban development depletes Colorado’s water resources by increasing demand for water (primarily for lawns) and by reducing natural supply (through the paving of natural recharge areas).

The report found that the total annual residential and commercial water use in the state would be 19 percent lower under a strategic growth scenario, as compared to business as usual. This is in large part because townhomes (which enable more homes built close together in a given area) use about 66% less water than a typical single-family home, and 90% less than a large single-family home. Reflecting those differences, water connection charges (tap fees) for single-family homes in the Northern Front Range can exceed $50,000 – a strikingly large number that reinforces how costly (financially and water-wise) this type of development is.

7. Conserving open land

The Strategic Growth scenario would reduce total land consumption by 36%, conserving Colorado’s precious natural and agricultural lands. Sprawl often requires paving over farmland and natural landscapes, both of which are typically net positive for local governments’ budgets because they contribute more in local taxes than the value of any local services they receive. For example, farmland costs $0.35 in public services for every $1.00 of revenue it generates for local governments, while residential development costs $1.16 in public services for every $1.00 of public revenue generated.

In Colorado, sprawl currently threatens:

- 420,000 acres of agricultural land;

- The $28.5 billion tourism industry, which is largely powered by the state’s gorgeous natural landscapes – not to mention permanent residents’ daily enjoyment of these areas; and

- Fragile ecosystems, as land use change is a top driver of biodiversity loss – fundamentally threatening climate resilience, both locally and globally.

For example, 777 Yarrow at Belmar Park in Lakewood is 411 apartment homes, built on 5 acres next to a large public park, 0.5 miles from Whole Foods and Target (enabling residents to walk for quick shopping trips). If that same number of homes were built as a typical suburban place type on the outskirts of Lakewood, they would take up 82 acres of open land (and add 4 million miles per year of driving).

8. Reducing wildfire risk and insurance costs

The Strategic Growth scenario would reduce development in the high wildfire risk areas by 7%. 2.5 million people – almost half of the state’s population – live in Colorado’s wildland-urban interface (WUI), i.e., the edges of developed areas. More than a million of these residents live in areas with a moderate to very high wildfire risk. And anyone who has lived in Colorado for more than a couple of years knows that it’s not just a risk – thousands of Coloradans have lived through fire disasters. For example, the Marshall Fire in 2021 destroyed over a thousand homes in Superior, Louisville, and Boulder County.

Without smart growth policies, we will continue to build more homes in wildfire-prone areas. And that increases home insurance premiums for everyone, even for those living in more wildfire-safe areas. Eventually, as we’re seeing happen in California, the home insurance industry will refuse to insure homes in high-risk areas – leaving devastated residents homeless and bankrupt.

9. Cutting planet-warming pollution

The Strategic Growth Scenario reduces greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from vehicles by 11.5% and GHG emissions from buildings by 23%. This impact cannot be discounted at a time when Colorado has just fallen short of its first major climate target. For more details on the climate benefits of smart growth, read our October 16, 2025 blog post.

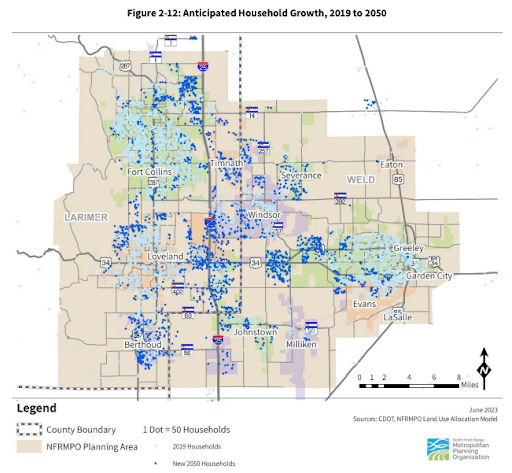

More sprawl on the horizon

The “business as usual” scenario that DOLA analyzed is playing out in real time across Colorado. The graphic below maps anticipated housing growth in the Northern Front Range with each blue dot representing 50 new homes. The majority of new housing is located on the periphery of existing municipalities like Greeley, Loveland, and Wellington – far from city centers, jobs, and transit. As outlined above, these developments are likely to require substantial new and costly infrastructure and services; increase household costs for housing, transportation, and energy; heighten wildfire exposure and insurance rates; generate additional traffic and pollution; and consume more land and water.

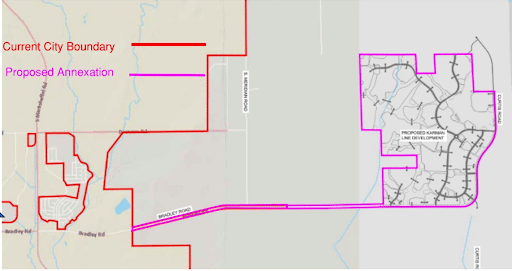

In contrast, recognizing the many costs of sprawl, voters overwhelmingly rejected a proposed “flagpole” annexation in Colorado Springs in June 2025. By a margin of more than 4:1, voters clearly indicated a preference for smart, incremental growth rather than adding unsustainable municipal responsibility for the Karman Line parcel – where a developer proposed building 6,500 homes on a 1,900-acre parcel. That would have been 3.42 homes per acre, equivalent to DOLA’s most harmful place type from a smart growth perspective: “large lot dispersed residential” places. The outcome of this vote shows that, when made aware of the negative consequences of sprawl, informed voters are strongly opposed to unstrategic growth.

Caption: A map from the Colorado Springs City planning department presentation showing the flagpole shape of the proposed Karman Line Annexation.

To be clear, Housing Forward Colorado is pro-housing. We are highly motivated by the state’s shortage of 106,000 homes, which will only get worse if new construction fails to keep up with population growth. However, we also advocate for growth strategies that minimize environmental impacts, reduce infrastructure and development costs, and lower household expenses for all Coloradans by directing new housing into existing cities in areas with available infrastructure capacity.

Colorado’s metro areas are abundant with unused or underutilized land that should be turned into housing, especially smaller homes on smaller lots that use land more efficiently and Transit-Oriented Development. This includes strip malls with shuttered storefronts as well as any kind of parking lot that sits empty, like the open seas of parking that surround big shopping malls. In addition, nearly 70% of residential land is locked up in single-family zoning, limiting housing choices and supply in walkable and high-resource areas. If a city determines that it lacks sufficient space for infill housing to meet its population’s needs, we recommend building on the margins – inching outwards incrementally rather than haphazardly approving “leapfrog” annexations.

What’s next?

DOLA produced its Strategic Growth Report, the basis of this blog, at the direction of a state law passed in 2024: SB24-174. That law also requires certain local governments to add Water Supply and Strategic Growth Elements to their Comprehensive Plans (starting December 31, 2026 and due every five years thereafter). The legislation requires Strategic Growth Elements to “discourage sprawl and promote the development or redevelopment of vacant and underutilized parcels in urban areas.” DOLA is currently developing guidance for that local government requirement.

In the next post in this blog series, we’ll cover the specific policies and financing tools that influence growth – such as metro districts, three-mile plans, annexation, impact fees, and Urban Service Areas. More soon!