Co-Authored by Luke Teater, Thrive Economics and Matt Frommer, Housing Forward Colorado

It’s no secret that Denver’s housing construction boom has caused average rents to fall across the metro area, as reported in several articles here, here, and here. In the last two years, average apartment rents have fallen 5.9% – a major win for housing affordability, especially since housing is the largest expense for most Coloradans. However, what hasn’t been sufficiently explored is how this building boom affected housing costs for low-income households.

To answer this question, we analyzed RealPage data from 851 Denver-area apartment buildings to measure the change in average rents from 2023 to 2025, allowing us, for the first time, to evaluate how specific segments of the Denver rental market were affected by the historically large wave of new apartments that opened during this period.

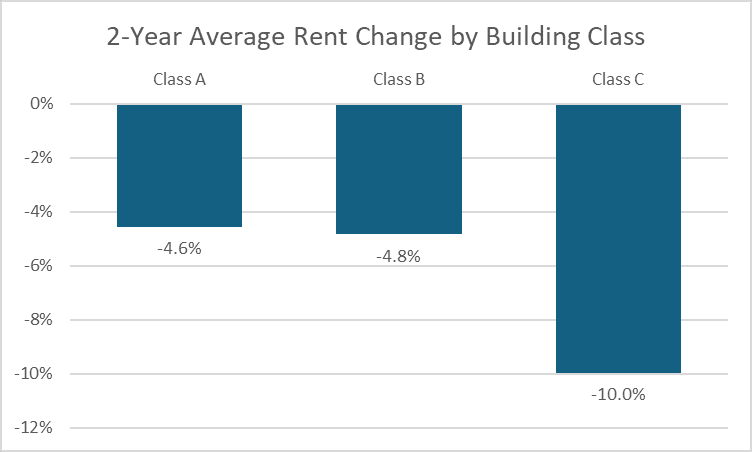

When we dug into the data, we found that Class C buildings (the most affordable segment, with buildings that tend to be older and have fewer amenities) saw average rents fall 10.0% over this period. This was more than double the decline for more expensive Class A or B apartments, which are newer and offer more amenities. This challenges the common narrative that building new market-rate housing only benefits high-income renters. Instead, when metro Denver built more housing, the steepest rent declines occurred in the older, more affordable properties typically occupied by lower-income renters. In dollar terms, residents of more affordable Class C apartments are saving $2,076 per year compared to rents in 2023, while the average Class A renter is saving $1,188. These rent savings are especially significant for the lower-income tenants who typically occupy Class C buildings.

| Building Class | Average Monthly Rent Q3 2023 | Average Monthly Rent Q3 2025 | Change |

| Class A | $2,174 | $2,075 | -$99 (-4.6%) |

| Class B | $1,882 | $1,791 | -$91 (-4.8%) |

| Class C | $1,735 | $1,562 | -$173 (-10.0%) |

Rent Declines By Building Class and Age

The rent impact of new housing supply varies significantly by building class, with lower-quality, more affordable buildings seeing the largest rent declines.

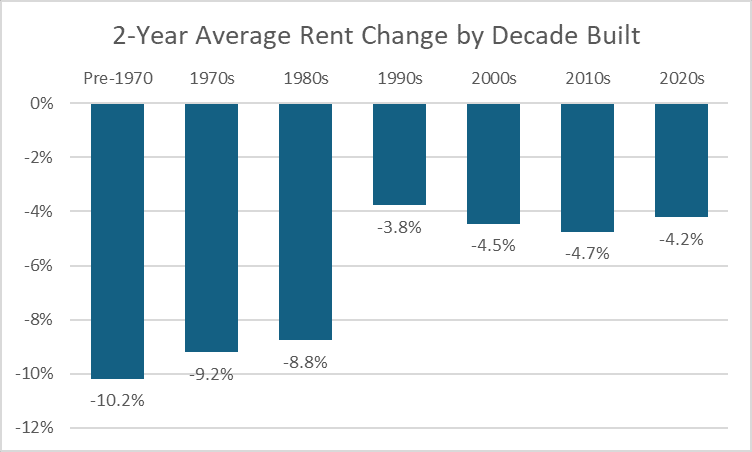

Additionally, older buildings experienced significantly larger rent decreases than newer buildings, despite the more direct competition that more recently constructed buildings face from brand new rental properties.

For the average renter in a Class C building, this represents more than $2,000 in annual savings – or more than a month’s worth of rent that can now be used for other basic needs like groceries, childcare, healthcare, or transportation. Those with the lowest incomes suffer the most from the housing shortage and would see the greatest benefits if it were resolved.

Boosting Supply is a Powerful Housing Affordability Strategy

When our policies don’t allow the market to build enough housing for middle- and upper-income households, those households don’t just disappear – they bid up the rents on existing housing that would otherwise be occupied by lower-income families, displacing low-income households and driving up rents in the most affordable parts of the market. In contrast, when we do build enough new housing, it creates more space for everyone and reduces rent pressures throughout the market, especially in its most affordable segments. The reduced cost and competition allows low- and middle-income renters the option of either saving money on rent or moving to higher quality homes and/or locations that may now be within their budget. This has long been understood in theory and academic research, but we are now seeing it play out in real-time in our own communities.

The surge of new housing construction in the Denver metro is lowering market-rate rents across the spectrum, pushing them into ranges that more households can afford. In affordable housing terms, the average Class C rent in this dataset was affordable to households at approximately 75% AMI in 2023, but fell to a level affordable to households at roughly 60% AMI by 2025. In other words, these homes were affordable to a two-person household earning the equivalent of $81,000 per year in 2023, but by 2025 they’re affordable to a household earning around $67,000. A market-wide rent decline of this magnitude, affecting hundreds of thousands of new and existing homes across the region, would have been prohibitively expensive to achieve through public subsidy alone.

Despite these recent rent declines, public subsidies remain critical. Families earning 30% of AMI still cannot afford even the lowest-priced Class C units in the dataset. These Coloradans need dedicated public investment through housing vouchers, rental assistance, and subsidized housing. However, market-wide rent declines like these do help these programs stretch further. When market rents fall by $175 per month, a rental assistance program that previously helped 100 families might now be able to serve 110 or 115 families with the same budget.

Another finding is that even the new apartments are relatively affordable for most Denver residents. There is a common assumption that all new apartments are “luxury” apartments that are only affordable to the ultra-wealthy, but the data show otherwise. Looking at only new buildings – those built in the 2020s – more than 85% of newly constructed apartment homes are affordable to the median Denver household (100% Area Median Income), and about half of all new apartment homes are affordable to households making 80% AMI.

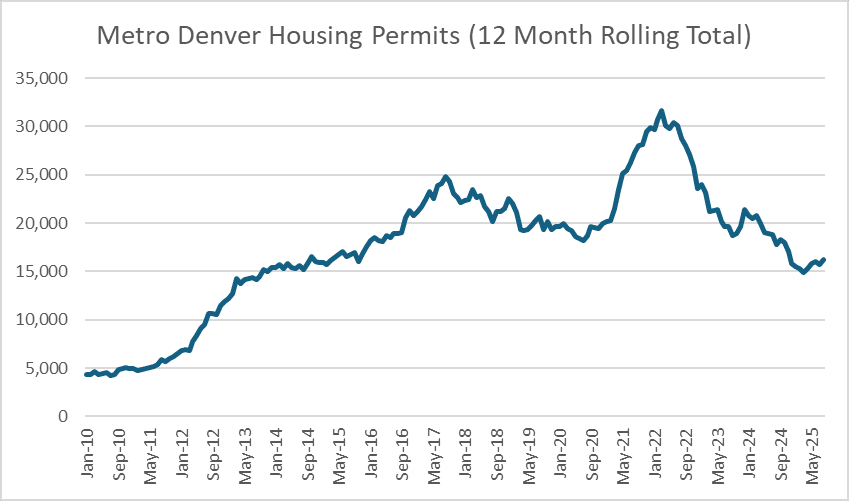

The Construction Boom – and Coming Bust

These rent declines are being driven by historic amounts of new housing supply. New housing permits surged to record levels in 2021 and 2022 as strong rent growth and low interest rates made it easy to finance new apartment projects. Since the housing development process can take several years, many of the new projects that began in 2021 and 2022 are now coming online and driving down rents across the market.

Source: US Census Bureau Building Permits Survey

But this situation will not last. Denver is still too expensive – rents are still 20% higher than in 2019 – and the housing development pipeline has dried up due to higher interest rates, increased construction costs, and declining rents, with few new projects starting. New housing permits in metro Denver have fallen to nearly half of their peak level. This will likely cause rents to rise again in 2026 and 2027, and again the most significant rent increases are likely to be seen in the most affordable segments of the market. We need sustained housing production in order to finally get renters off this rollercoaster and make Colorado affordable in a permanent way.

City and state leaders who want to improve housing affordability in their communities should carefully consider this. Denver’s recent experience shows that when we build more housing, rents fall – and they fall the most for households that need the greatest relief.

_________________________

*This analysis examines RealPage rent data for 851 Denver metropolitan area apartment properties (buildings with 50+ units) that have complete asking rent data for 2023-2025. Properties are classified using RealPage’s standard definitions: Class A (newest/highest quality), Class B (mid-market), and Class C (older/most affordable).

To receive news and analysis from HFC, subscribe at the bottom right of this page!