Key Takeaways:

- Local housing needs assessments across Colorado consistently identify lack of housing diversity as a problem, and specifically lower cost smaller and mid-form homes.

- Portland’s recent reforms, which enable smaller homes on smaller lots, significantly increased the production of more affordable housing types, such as duplexes and townhomes, which are selling for $300,000 or more below single detached houses — a model Colorado cities can learn from.

- Neighborhood impacts have been modest, with little evidence of displacement or geographic concentration of new development.

Across Colorado, cities and towns are rethinking how neighborhoods are built. Communities like Lakewood and Denver are exploring changes to zoning rules to allow more diverse housing types like duplexes and cottage clusters in areas historically reserved for one single detached home per lot. These reforms are gaining traction as local leaders seek solutions to a growing and urgent challenge: Colorado’s persistent housing shortage and lack of housing choice.

Colorado communities can learn from places that have taken the leap. Portland, Oregon, offers one of the most comprehensive and well-documented examples of middle housing reform to date. “Middle housing” refers to small-scale, multi-unit homes that occupy the gap between single detached houses and apartment buildings. Portland enacted sweeping middle housing reforms in 2021 and 2022, opening up neighborhoods previously reserved for single detached houses to a broader range of these housing types. This post summarizes the early outcomes of Portland’s reforms and the lessons they offer for Colorado communities.

Colorado has a shortage of housing and of housing diversity

The need is clear: Colorado is currently short by about 105,000 homes of what would be considered a stable housing market. In the decade leading up to 2020, our population grew by 14.8% but our housing stock increased by only 12.6%. Without a change of course, the shortage will get worse; the population is expected to grow another 1.7 million by 2050, with nearly 90% of that growth concentrated along the Front Range. Over the last decade, housing prices in the Denver metro area nearly doubled, from around $285,000 to over $568,000 per home. Higher housing costs result in rising evictions, homelessness, and people leaving the state. Today, nearly half of Coloradans are cost-burdened, spending over 30% of their income on housing.

The problem is not just the number of homes—it’s also the kind of homes being built. Much of the new housing being built falls at two extremes: sprawling subdivisions of large individual houses far from jobs and shops, and small rental units in big apartment buildings. These housing types fail to meet the needs of many Coloradans. The 65 and over population is projected to double by 2050, with many older adults and empty nesters looking to downsize from their oversized homes while staying in their communities; one reason AARP has made middle housing a top policy priority. Households of all ages are shrinking in size; approximately two-thirds of homes in the Denver region now house only one or two people. Many families with younger kids are left without options after outgrowing their apartments yet unable to afford a house in their community, contributing to declining enrollment and school closures. This lack of housing diversity is consistently identified in local government housing needs assessments as a mismatch between our housing stock and the demand.

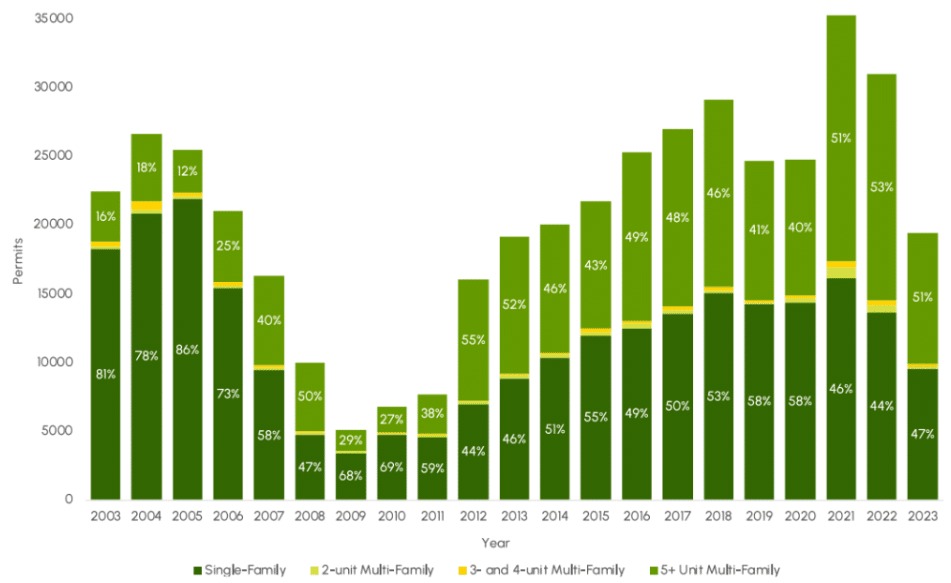

Middle housing types made up a significant share of national housing production through the 1980s, but the share has since declined by 90%. In Colorado, buildings with 2-4 units accounted for just 2.5% of housing permits over the last decade (SWEEP analysis of HUD data). These housing types are familiar to most of us, as many older neighborhoods we know and cherish already include middle housing built before it was banned by single-unit zoning. New development has continued to be predominantly single detached houses, which are generally more expensive and less sustainable. Today, re-legalizing middle housing offers a path toward more affordable rents and attainable homeownership, walkable neighborhoods, and sustainable development.

Denver regional housing production by scale (DRCOG)

The Portland area shares key housing market characteristics with Colorado’s Front Range, including rising prices and limited housing choices. Portland’s middle housing reforms were aimed at addressing these familiar challenges. Even as Colorado advances transit-oriented development, single-unit residential neighborhoods still account for the majority of urban land—about 77% in Denver—leaving further opportunity to expand housing choice within existing communities. In these areas, the zoning status quo tends to incentivize luxury rebuilds over more affordable and diverse housing types, contributing to rising costs and missed opportunities for inclusive growth.

Portland’s planning department recently released a three-year progress report on its middle housing reforms through June 2024, offering valuable evidence for Colorado cities considering similar steps. The report analyzed building permits and development outcomes in formerly single-unit zones, tracking how the reforms have affected housing production, affordability, and neighborhood change.

What were the results of Portland’s reforms?

A modest increase in housing production tucked into existing neighborhoods: Before reform, housing in single-unit zones was limited to one house and an Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) per lot, and in some cases duplexes on corner lots. The share of city-wide housing production in these areas grew from 16% pre-reform (2018-2020) to 27% (2023-2024), resulting in more home choices in existing neighborhoods near jobs, transit, schools, and other daily needs. Portland issued building permits for approximately 1,400 middle housing units and ADUs over the three-year period, including 600 in 2023 alone, the first full year of implementation. For context, Portland’s population is about 630,000; roughly 90% the size of Denver and four times that of Lakewood.

More diverse housing types: Middle housing now makes up over half of new homes in these areas. Fourplexes were initially the most popular form, but cottage clusters (a group of detached homes grouped around a shared outdoor space) have recently become most common. The typical unit built is a 900 square foot, two-bedroom, for-sale unit. Single detached houses are still being built, but now make up just 20% of new homes in these zones.

Increasing housing diversity

More attainable prices: Middle housing has helped bring back price points that had largely vanished from many Portland neighborhoods. By distributing land costs across multiple smaller homes, developers have delivered new middle housing units that sell for $300,000 less than new single detached houses at market rates: around $600,000 compared to $900,000 per home. Income-restricted homes supported by the city’s affordable homeownership programs sold for an average of $353,000, and with much higher volume than pre-reform.

Middle housing sells for $300,000 less than single detached houses

Middle housing reforms have unlocked homeownership opportunities for lower- and middle-income families across the city, including in designated “higher-opportunity” neighborhoods—areas with strong access to education, jobs, and transit. Prior to these reforms, applications for the city’s affordable homeownership programs were virtually nonexistent in these neighborhoods because homes there were too expensive to qualify for affordability programs. There were 66 such applications in 2023, with 2024 trending higher through a half-year of data. This progress supports one of the city’s key equity goals: placing affordable homes in areas of opportunity. These affordability programs include a 10-year property tax exemption and a system development charge (SDC) exemption (mainly parks, transportation and water and amounting to tens of thousands of dollars) for income-qualified buyers (100% AMI) or renters (60% median family income).

Notably, over half of middle housing units have been built on their own lots. This is enabled by an expedited middle housing land division process, which allows ownership without the complexity and cost of condo associations and HOAs, instead relying on simpler maintenance agreements or common-element easements.

Has middle housing reform led to more displacement and demolitions?

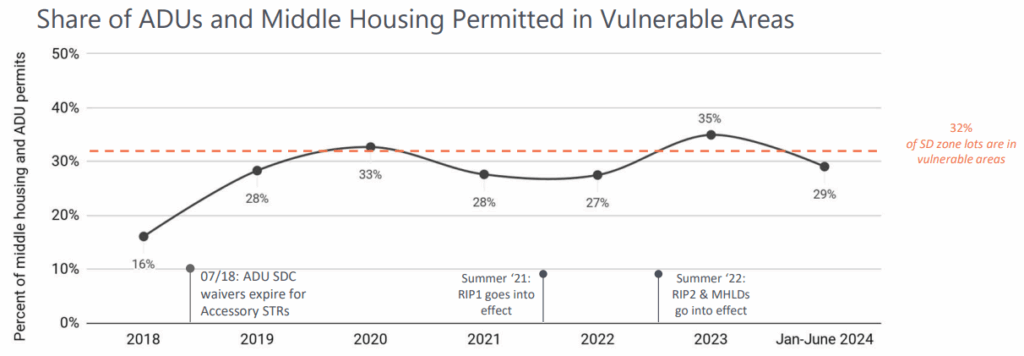

An even geographic distribution across neighborhoods: Concerns about displacement and uneven development were common during the reform process. Results so far show that new housing has been relatively well-distributed. Neighborhoods identified as being more vulnerable to displacement have seen development in proportion to their share of lots, while high-opportunity areas saw slightly more than their proportional share. Development has also shifted marginally away from designated historic areas.

Distribution throughout the city

The city conducted a displacement risk analysis when considering these reforms, predicting an overall reduction in displacement for low-income renters. When lawmakers considered exempting vulnerable areas from middle housing rezoning, the Anti-Displacement PDX coalition opposed it, arguing that “increased housing opportunity is needed in all neighborhoods in order to reduce upward pressure on housing costs and rents” and that “attempting to reduce displacement pressure in the short-term using a tool that limits housing opportunity and exacerbates spatial disparities in the long-term is counterproductive.”

Middle housing has not concentrated in vulnerable areas

Demolitions have not increased: One concern with upzoning is that it can incentivize demolition of older homes, so it is notable that demolitions have not increased since the reforms. Where demolitions have occurred, the number of homes per lot has increased from an average of 1.64 in 2018 to 3.88 in 2024, realizing the goal of creating more housing where demolitions do occur and interrupting the pre-reform norm of building ever-larger single detached houses. In other words, middle housing projects have more than doubled land-use efficiency on redeveloped lots.

What specific policies enabled middle housing?

These key reforms were implemented in two phases in 2021 and 2022:

- Legalizing middle housing types, including duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, townhomes, and cottage clusters on lots previously zoned for single detached houses and ADUs. Sixplexes are also allowed if half of the units meet affordability requirements.

- Graduated building size limits that rise with unit counts, as measured in floor area ratio (FAR), the building’s floor area relative to the lot size. For example, in Portland’s common R5 zones, on a 6,000 sqft lot a single detached house is capped at 0.5 FAR or 3,000 sqft, a duplex at 0.6 or 3,600 sqft, three units at 0.7 or 4,200 sqft, and four or more at 0.8 or 4,800 sqft.

- Eliminating off-street parking requirements in single-unit zones. Notably, 75% of middle housing units were built without additional parking. (SWEEP recently published a Colorado Parking Reform Primer here to explain the benefits of eliminating minimum parking requirements).

- Allowing two ADUs per lot along with a primary unit.

- Introducing the Middle Housing Land Division process for expedited lot splits, exempt from most typical approval criteria.

- Aligning height limits, setbacks, and dimensional standards to ensure practical and financial viability.

Environmental and public finance considerations

The benefits of middle housing go beyond affordability. Building more homes within existing neighborhoods also supports sustainability and fiscal health.

If current trends continue, nearly half of Colorado’s new homes by 2050 will be built outside of urbanized areas on open space and natural lands, far from jobs, transit, and services. In the Denver region, developed land has increased by 22% over the past two decades, largely due to exurban sprawl. Sprawling development uses more water, energy, and infrastructure, while generating 30% more driving per household. In contrast, compact housing types are much more efficient, typically using 30–55% less energy and 63–86% less water.

Compact development also strengthens municipal finances. A typical fourplex in Portland, using cost data described above, adds $2.4 million to the property tax base, compared to $900,000 for a new single detached house. On the other side of the ledger, infrastructure costs are also lower when homes are built in existing neighborhoods. This is especially salient in Colorado given TABOR’s constraints, rising infrastructure and insurance costs driven by natural disasters, and emerging metro district solvency issues.

Middle housing takes many forms

Colorado’s needs and opportunities

Across the state, local housing needs assessments (HNAs) consistently identify middle housing as a missing piece in their communities:

- On the West Slope, Grand Junction’s 2024 Housing Strategy Update includes exploring the option of creating pre-approved plans for ADUs, townhomes, and duplexes to facilitate production of middle housing. Cortez’s 2023 HNA recommends “increasing the types of housing allowed in all districts, including duplexes, townhomes, and multi-family.”

- In Southern Colorado, a 2024 Pueblo plan identifies potential to “revise zoning regulations to improve the ability of developers to build missing middle housing.”

- In the Denver metro area, Thornton’s 2024 draft HNA lists a shortage of middle housing as a key finding, noting that it is “crucial for addressing affordability and diversity in housing options.” Superior’s 2025 HNA calls for “allowing moderate density increases in single-family zones to allow for duplexes and triplexes” and developing pre-approved plan sets for desired housing types, such as middle housing and ADUs.

The Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG) Regional HNA notes: “Much of the new housing in the region does not support the diversity of housing needs across all income levels and household types.” It identifies barriers including “zoning that supports a narrow range of housing types,” which “limits the land available for more housing production and options,” and off-street parking requirements that “limit housing production by making many types of housing infeasible in many locations.” Similar findings are common throughout Colorado’s local HNAs and strategic plans.

With these needs and barriers in mind, several Colorado cities are weighing middle housing reforms. This movement is backed by public opinion: a 2024 Zillow survey found that Americans support allowing ADUs and duplexes/triplexes in their neighborhoods by about 70% and 60% respectively, with stronger support for both among Colorado respondents. Middle housing complements strategies already in use. HB 24-1313, a key housing law, focuses growth in transit-oriented areas. A fourplex on a 6,000 square foot lot amounts to about 30 units per acre, demonstrating how middle housing can be a part of transit-friendly development.

Lakewood’s proposed zoning code update would allow middle housing types in all residential neighborhoods. It would allow buildings to be incrementally larger if they contain 3 or more units, though even these would not be larger than buildings currently allowed. Importantly, it would allow smaller lots to accommodate smaller homes and scale down parking minimums that often render potential housing development infeasible. Doing so would open up a lot of housing opportunity as about 60% of Lakewood’s residential lots are over 9,000 square feet. (SWEEP wrote about Lakewood in April 2025). This would advance goals established in the city’s 2024 Strategic Housing Plan, which states: “Facilitating a wider range of housing options – especially smaller-scale options – is one way to support broader affordability within Lakewood and to ensure that long-time residents who want to remain in the community have viable housing alternatives.” The plan notes that existing middle housing currently sells for two-thirds the price of single detached houses.

Middle housing units in Lakewood are comparatively affordable

Denver is exploring a similar zoning code update to allow middle housing forms in residential neighborhoods through it’s Unlocking Housing Choices initiative. This proposal is complemented by another pending policy to eliminate minimum parking requirements. According to DRCOG projections, Denver is expected to add about 100,000 homes by 2050.

Colorado communities are actively searching for tools to ease the housing shortage, and middle housing is among the most promising. These smaller, more attainable homes can fit seamlessly into existing neighborhoods while expanding options for residents of all ages and incomes. Portland’s experience shows that smart reforms can deliver more homes, lower prices, and greater access to opportunity. As Colorado continues to tackle its housing crisis, middle housing offers a tested, scalable model that more cities can adopt.