Introduction

As the state prepares to release the Strategic Growth Report required by SB24-174 at the end of this month, it’s worth revisiting why strategic growth matters in the context of climate policy. Next month, we will publish an analysis of the final Strategic Growth Report in the context of Colorado’s urgent housing needs and climate goals.

The Challenge

“Strategic growth,” also known as “smart growth,” refers to the construction of housing within urban areas near jobs, businesses, transit, and existing infrastructure rather than in sprawling developments on open space and natural lands. The connection to climate isn’t always intuitive, but as environmentally-driven urbanists, we at Housing Forward Colorado take a holistic view of the climate crisis. We think strategically about how and where we can make the most positive impacts to turn back the tide of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Given the federal administration’s attacks on climate policy, smart growth is an essential and timely tool for near-term environmental protection and long-term climate resilience in Colorado.

Transportation is Colorado’s largest source of GHG emissions and one of the toughest sectors to decarbonize. That’s why we seek to change the way communities are built: so that people simply don’t have to drive as much. We envision a world where anyone who wants to can live in a compact neighborhood with jobs and services nearby. We envision a neighborhood where you can walk, bike, or take transit to your daily destinations – and drive fewer miles overall. In the face of an expected 30% population increase (1.7 million people) by 2050, Colorado needs policies that accommodate growth without increasing car reliance or sacrificing our precious open spaces and agricultural lands. Smart growth enables us to achieve this without adding undue stress to local infrastructure and municipal finances.

The Analysis

In Nov. 2024, the Colorado Energy Office (CEO) published a study that modeled three residential development scenarios in the state:

- The Baseline Scenario assumed recent local land use laws prior to the 2024 legislative session.

- Scenario A included enabling policies for accessory dwelling units and transit-oriented development.

- Scenario B added several other policies to Scenario A, including enabling multi-family housing along commercial corridors and minimum parking requirements reform – similar to those adopted by the state in 2024 (listed at the bottom of this article).

Incorporating zoning, market rents and prices, land costs, population projections, and other inputs, the analysis determined how many homes of different types would be feasible to develop in different locations across the state under each scenario – and what the expected greenhouse gas emissions would be for each.

CEO’s study was unique and particularly valuable because it incorporated real estate market dynamics. Similar studies used hypothetical land use scenarios without considering market feasibility. Nor have other studies focused on the specific land use changes (and GHG impacts) that could stem from a specific set of feasible land use policy changes. Despite these improvements to older analyses, CEO’s results “were within an expected range compared to similar analyses.”

After examining 7 different smart land use policies (listed at the bottom of this article), CEO’s study found that the most impactful policy changes modeled were transit-oriented development, removing minimum parking requirements, and encouraging ADUs – theoretical but somewhat different versions of the policies the state passed last year. These policies reinforce one another in making more affordable, climate-smart housing development and urban planning possible. And when cities opt to combine the most expansive versions of these policies, the positive impacts are exponential.

This report is a call to action for Colorado municipalities to continue implementing the state’s 2024 housing and land use laws, and also to consider other strategic land use policies that further expand housing options and prioritize new growth inside our cities rather than on open space.

Top 5 Takeaways: How Smart Land Use Policies Tackle Climate Change in CO

-

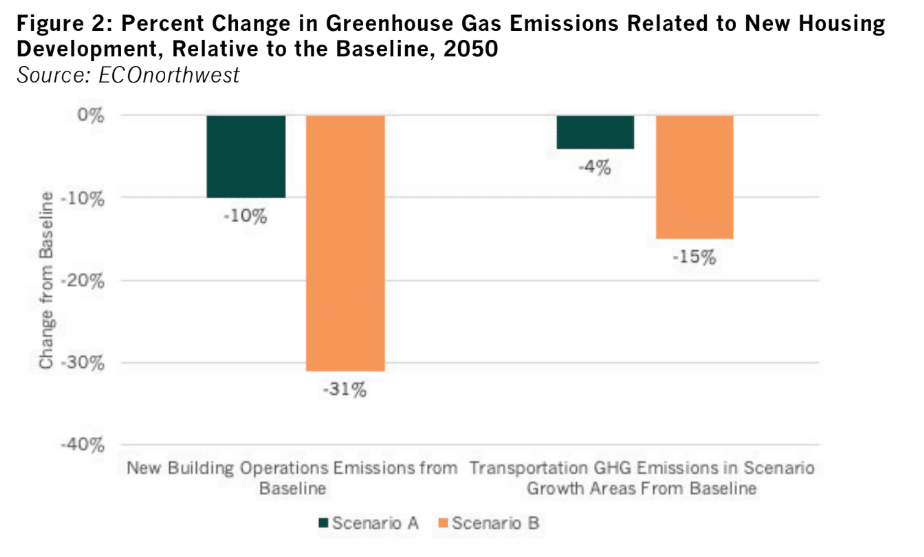

Cutting emissions from transportation by at least 15 percent in high-growth areas

Smart land use policies enable more people to live closer to destinations like neighbors and friends, jobs, shopping, and services. The closer you live to your destination, the easier it is to get there by walking, biking, and other eco-friendly transportation options. At the very least, it reduces the distance required to drive.

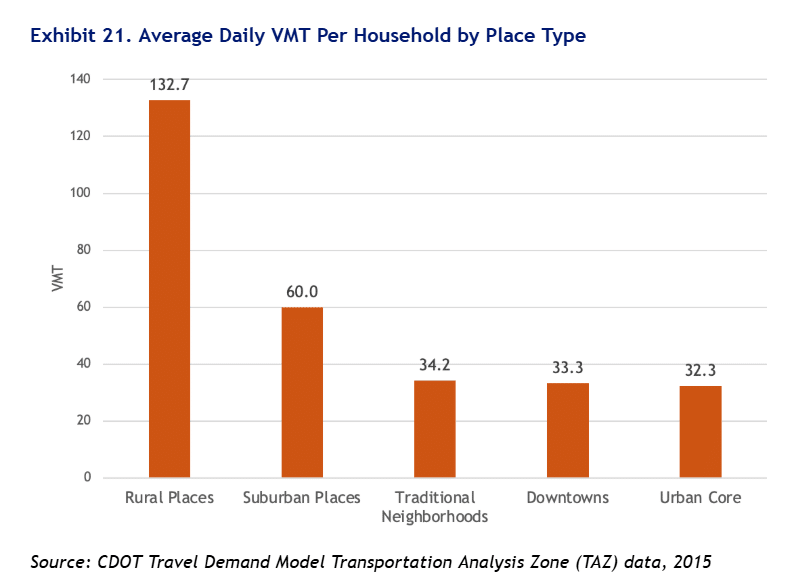

Below: Coloradans living in the suburbs drive twice as much as those living in urban neighborhoods.

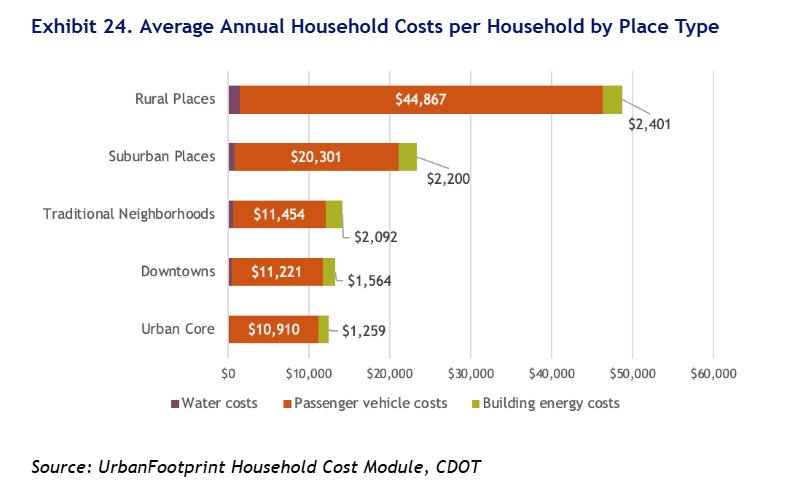

With this in mind, HB24-1313: Housing in Transit-Oriented Communities, a state law passed last year, requires jurisdictions in the fast-growing Front Range to allow for an average of 40 homes per acre in areas well-served by transit. The Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) has found that Coloradans in downtowns and traditional neighborhoods drive half as much as those in the suburbs. In CEO’s Scenario B (modeling policies similar to HB24-1313 and others passed by the state in 2024), the fastest-growing areas of Colorado saw a 15% reduction in household transportation emissions associated with new development as compared to the “business as usual” baseline scenario. Importantly, walkable and transit-friendly communities improve health through physical activity, save Coloradans money on transportation, and minimize the dreadful hours wasted stuck in traffic.

Basically, the closer people can live to their daily destinations, the less they have to drive – and the less GHG emissions they produce from transportation. We advocate for EV adoption while also working to reduce GHG emissions from the many gas-powered vehicles still on the road.

-

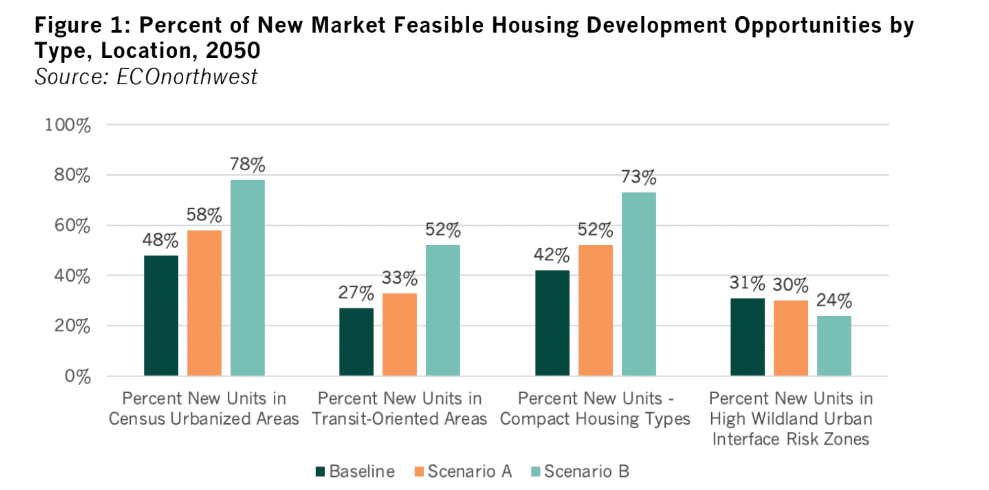

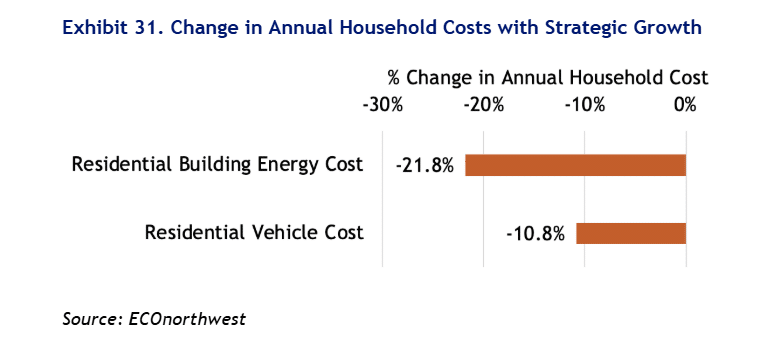

Cutting emissions from buildings at least 30 percent

Across CEO’s scenarios, smart land use policies changed the types of new homes that are built, enabling more compact housing types such as townhomes, ADUs, and multifamily housing. In the baseline scenario, these housing types comprised 42% of new units by 2050, while in Scenario B they made up over 73%. In contrast, the baseline predicted twice the number of new single family detached homes expected to be built, as compared to Scenario B.

Not only are compact and multifamily housing types more affordable, but they also tend to require significantly less energy to heat and cool due to their smaller size and shared walls (and sometimes floors and ceilings). CEO’s Scenario B was predicted to reduce all new housing’s building operations emissions (emissions from energy usage to power homes, including electricity) by 31% relative to the baseline. While our colleagues at SWEEP work to establish stronger building codes and more carbon-neutral building materials for all homes, we at Housing Forward Colorado advocate for these naturally energy-efficient smaller housing types.

Because they can be built closer together and nestled within existing urban neighborhoods, more compact homes also reduce driving.

-

Reducing exurban sprawl: protecting municipal finances as well as public open space

CEO’s baseline scenario predicts that more than half of new homes will be built on greenfield (currently undeveloped) sites outside the built footprint of the metro area. On the flip side, in Scenario B, infill (development in Census urbanized areas) was nearly 80% of residential development. This difference – supported by a modeled policy applying higher fees for greenfield development – is hugely impactful for two main reasons. Perhaps most obviously, it protects open spaces including natural and agricultural areas. Less obvious but still essential is that it protects municipal budgets and taxpayers from the high cost of new infrastructure spread out over greater distances.

Preserving open spaces is important for many reasons – including being able to enjoy nature, having land to grow food, and protecting local ecosystems. Land use change is a top driver of biodiversity loss, fundamentally threatening global climate resilience. And it’s not an exaggeration to say that sprawling patterns of growth pose an existential financial risk to municipal finances. Current and future taxpayers will be saddled with the costs of all those extra roads, utility lines, and public services needed for exurban development – when we could be using space more efficiently and building homes in areas that already have complete infrastructure.

We advocate for smaller homes on smaller lots, multifamily housing, and parking reform – all of which protect trees and natural lands within cities as well as outside them, by accommodating more homes on less space and preventing greenfield development. Adding housing near urban parks increases access to nature while simultaneously protecting open spaces. This benefits human health, happiness, and overall wellbeing while protecting ecosystems.

-

Improving climate resilience by protecting Coloradans from wildfire

In the face of more frequent and more intense climate disasters – especially wildfires, in Colorado – human lives and property are at even greater risk in Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) areas. Smart land use policies shift development towards infill areas and away from high WUI risk areas. As compared to the baseline, CEO’s Scenario B predicts a 7% overall shift away from high WUI risk areas towards more central and protected locations. Some areas see much greater outcomes; for example, Colorado Springs sees a WUI development drop by 27 percentage points: from 49% in the baseline to 22% in Scenario B. That represents almost 30,000 households (note that includes entire families, not just individuals) that would be living in a high wildfire risk area under a “business as usual scenario,” but instead would live in a low wildfire risk area thanks to strategic growth policies.

These changes will prevent loss of human life and property and improve community resilience while protecting wildlife and ecosystems. The Marshall Fire in 2021, which destroyed over 1,000 homes, demonstrated just how quickly suburban developments in WUI areas can burn. Wildfire risk also drives up insurance costs, public costs for fire-fighting infrastructure and services, and increased demand for scarce water resources. Colorado’s average homeowners insurance increased 52% between 2019 and 2022 partly as a result of wildfire risk and are now 87% above the national average.

-

Even greater impact when combined with investments in public transit

Smart land use policies enable more people to live closer to transit, which makes it a more convenient and more likely travel option. In fact, living within a 10-minute walk (1/2 mile) makes people four times more likely to use transit daily.

In CEO’s baseline scenario, only one-quarter of residential development is forecast in transit-oriented areas. In Scenario B, the share is more than half. This results in 43,000 daily trips shifting from a single-occupancy vehicle to an alternative (transit, biking, walking, etc.). That’s part of a 16% increase in boardings statewide, compared to the baseline – including an estimated 26,000 daily work trips on public transportation. And those trips most likely are replacing costly commutes in cars.

Furthermore, enabling people to live closer to transit creates a positive feedback loop that directly improves the transit service. When more people ride a bus or train, the transit system sees more revenue and becomes more cost-effective, and the higher demand leads to better service.

And transit ridership shoots up even higher when the smart land use policies from Scenario B are combined with reasonable investments in transit. CEO created a “Scenario C,” modeling changes in transit ridership based on Scenario B’s policies plus the launch of the proposed Mountain Rail service and doubling statewide transit service by 2050, as compared to 2019 levels (applied evenly to routes and transit agencies statewide). Statewide ridership was about 28 percentage points higher from Scenario B to Scenario C (and a 44% increase from baseline). Such investments are not just pie in the sky – the state is actively increasing transit funding with support from CDOT’s new $110 million transit grant program, which kicks off in 2026, and nearly $58 million for transit and rail from the SB24-184 rental car fee, though we’ll need to invest much more to achieve the transit service envisioned in Scenario C.

CEO took the additional step of modeling the impacts of making transit service completely free to users. With that policy change layered on top of Scenario C, boardings increased by 75% from the baseline – about 53 percentage points higher than Scenario B’s land use policies on their own.

CEO wrote that GHG outcomes of these transit-focused scenarios was “somewhat modest,” as measured by the expected reduction in driving. However, CEO’s models did not include changes in employment and school locations, which would typically accompany changes in housing locations – nor did they include emissions reductions from carbon stored in agricultural and undeveloped areas (e.g. in the soil and trees). CEO’s results represent a conservative estimate, and including those additional factors would likely increase the predicted reduction in GHG emissions.

What’s Next?

This study demonstrates that Colorado’s recent land use reforms, and potential additional steps that could be taken in the future, have the potential to substantially reduce our GHG emissions. Our trajectory is strong with the transit-oriented development law and ADU and parking reforms passed at the state level last year, but there’s much more that can be done. The Housing Forward Colorado team has been tracking municipalities’ responses to those 2024 state laws and most recently published a report in August 2025.

First, cities need to implement these policies to their maximum capacity. For example, state law (HB24-1313) requires multifamily housing to be allowed in well-served transit areas, but CEO’s study used a broader radius for that policy: ½ mile as compared to the state’s ¼ mile. The study also included policies that allow multifamily housing in commercial corridors. Similarly, the state’s parking reform (HB24-1304) applies to a much smaller geographic area than what was modeled in the study. Cities and counties across the state have the opportunity to join Denver, Boulder, Longmont, and others to go beyond the state’s minimum requirements by applying parking reforms and loosening residential zoning restrictions in much broader areas. Parking requirements, in particular, are the most impactful land use policy that inhibits smart growth – and thus they represent the greatest opportunity to unlock climate-smart housing construction within urban and suburban areas.

Furthermore, it’s not enough just to allow more urban infill. We also need to update our land use policies to discourage dispersed low-density greenfield development on open space and natural lands. We can do this by better aligning impact fees, infrastructure financing tools, and annexation and growth policies with smart growth principles.

Aside from broader parking reforms and more transit-oriented development, possibly the biggest frontier of land use policy reform in Colorado is what’s called “missing middle” housing. This is a policy factored into CEO’s Scenario B but not included in the legislature’s 2024 package of land use reforms. “Middle housing” is anything between detached single-family homes and large apartment buildings; it includes duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, townhomes, cottage clusters, and small apartment buildings. It’s called the “missing middle” because current zoning policies ban it in most residential areas – despite the high market demand for these housing forms, which tend to be more affordable than single family homes (due to their smaller size, among other reasons). Local jurisdictions should join pioneering Lakewood in legalizing the missing middle, enabling these climate-friendly housing types to provide naturally affordable homes to more people.

Conclusion

In a federal landscape where key climate and environmental policies are being rolled back, environmentalists and climate advocates have an opportunity to unlock different, impactful solutions that are not yet overly politicized and are controlled at the state and local level. While we strive to defend and restore the existing policies under attack, we can also push forward and expand new policies that might be more feasible in this tense moment. Those new, impactful solutions must include land use reform. In the face of simultaneous affordability and climate crises, these policies have the double benefits of reducing housing costs and transportation costs while also reducing GHG emissions. The need is immense, and the opportunity is clear.

Appendix: Policies considered in the CEO study

- Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs): Allows one ADU per parcel with no parking required where single family homes are allowed

- Transit Oriented Development: Allows multifamily housing by administrative approval within ½ mile of rail stations and ¼ mile of high-frequency bus and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT)

- Resort affordability: Allows multifamily housing and applies incentives for workforce/affordable housing near high-frequency bus stops, BRT stops, or in commercial corridors in Rural Resort Job Centers; models meeting DOLA-estimated Proposition 123 commitments

- Missing middle: Allows duplexes, triplexes, and townhomes in single-family-housing- zoned residential areas of urban municipalities

- Multifamily housing (MFH) in commercial corridors: Allows MFH on parcels zoned for office, retail, and mixed use along arterial roadways and local bus lines, in urban and suburban municipalities

- Eliminate parking minimums in residential areas of urban municipalities where policies 2, 4, and 5 apply

- Greenfield costs: Applies higher fees for development outside of Census Urbanized Areas

In summer 2024, Colorado passed a suite of smart land use laws quite similar to those studied in the report. They include:

- Transit-oriented communities: allowing multifamily housing near well-served transit stops

- Removing minimum parking requirements for multifamily housing near transit

- Legalizing and streamlining approvals for ADUs.

If you have questions or comments about this blog post, please email cleland@swenergy.org.