April 21, 2025 | Matt Frommer, SWEEP & Luke Teater, Thrive Economics

Lakewood is considering important policy reforms to address its housing affordability crisis and advance the city’s goals around transportation, climate, and quality of life. As city leaders develop strategies to increase housing choices and affordability, there’s been widespread debate about the nature of the housing crisis and how to fix it.

It’s no secret that housing prices in Lakewood have skyrocketed over the last 8 years. Since 2017, the average home price in Lakewood has increased from $350,000 to $590,000, far outpacing wage growth. The housing crisis affects everyone – from young professionals priced out of homeownership, to families spending over half their income on rent, to longtime residents facing displacement. Essential workers like teachers, childcare providers, and retail staff can’t afford to live where they work.

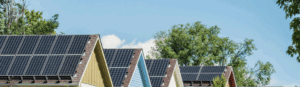

Over half of Lakewood renters are “housing cost-burdened”, spending more than 30% of their income on housing. Around one-quarter spend over half their incomes on rent. This often forces low-income families to choose between paying the rent and other basic needs like groceries, medical bills, and utilities.

Source: Denver Regional Council of Governments Housing Needs Assessment Dashboard

The Homebuilding Rollercoaster

While many factors contribute to rising housing prices, the primary driver is Colorado’s housing shortage caused by years of underproduction. From 2010 to 2020, Colorado’s population grew by 14.8% but its housing stock increased by only 12.6%. By 2019, Colorado was short 127,000 homes. On top of the housing shortage, the 2020 COVID pandemic led to a historic increase in household formation as individuals moved out of shared living situations and family homes in search of their own homes. Remote work also allowed people to live further away from jobs and seek more spacious homes to work from home, increasing demand for housing in suburban communities like Lakewood.

Source: Denver Regional Council of Governments Housing Needs Assessment (2024)

When demand (Coloradans needing homes) grows faster than supply (homes available), it creates a scarcity that leads to cutthroat competition for a limited number of homes – and then prices spike. Low housing inventory forces high earners to bid up the price of homes that would otherwise be available for middle-income households – and this goes on down the line until low-income families are priced out, displaced, and in the worst cases, forced into homelessness. It’s a cruel game of musical chairs, as illustrated in this short video by the Sightline Institute.

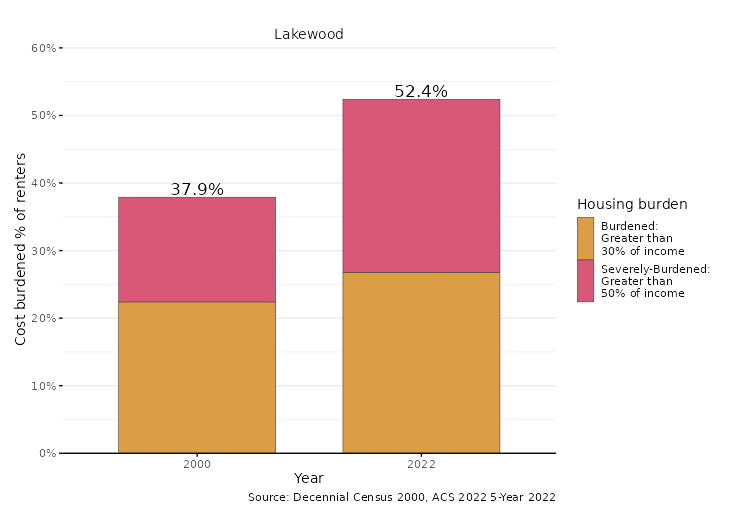

Ok, but haven’t we been building tons of new housing in Colorado recently?

Surely, Coloradans have noticed all the big cranes dotting the Denver skyline over the last few years. In 2021, record-low interest rates led to a building boom and Denver’s apartment construction nearly doubled the previous decade’s annual average. As a result, rents plateaued, then decreased by 1.5% over the last year. While this is welcome relief for renters, it’s a drop in the bucket compared to the 32% increase in Denver-area rents from 2017 to 2023.

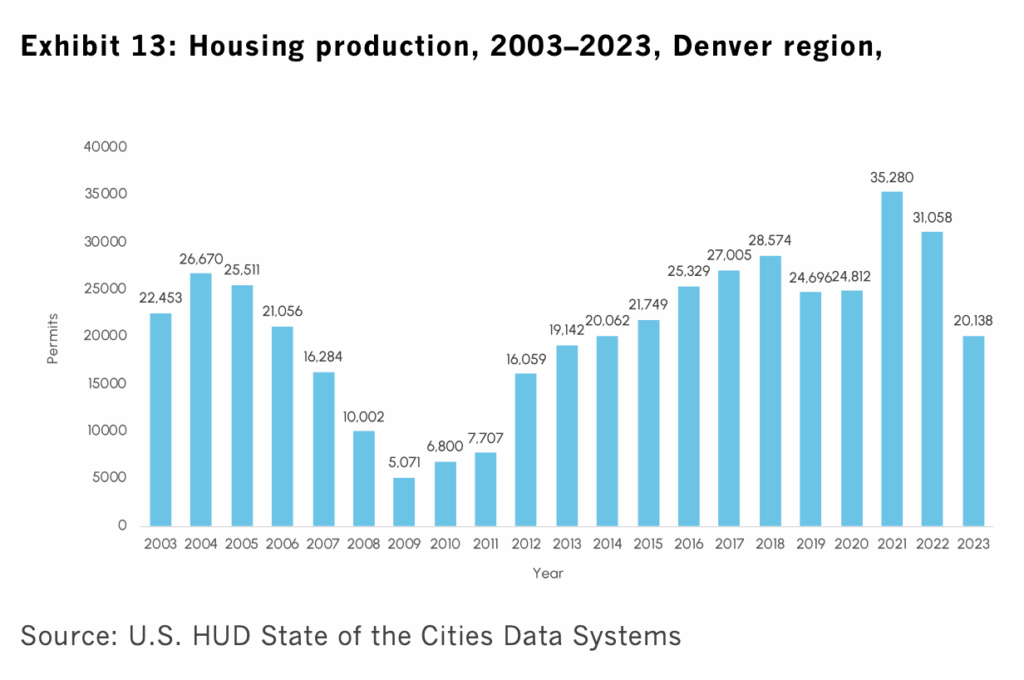

In other cities, increased housing production has produced more dramatic results. For example, Austin, Texas saw a population boom during the pandemic along with a corresponding rise in housing costs. The city responded with a major surge in homebuilding, expanding housing availability and leading to a 22% decrease in rents in 2024. (Notably, this is often framed as a negative by developers – a “painful” or “worrisome” market trend – despite the positive affordability benefits for households across the region.)

This graph shows how rent growth drops when vacancy rates increase; renters hold more market power when there is less of a housing shortage. Source: Austin Investors Feel Pains of Overbuilding

While Colorado’s housing construction has picked up over the last few years, it’s still working from a place of historic underproduction. More recently, rising interest rates have slowed momentum and Denver apartment permits in 2024 dropped 82% below their 2022 peak. This trend, if sustained, will worsen future shortages, causing rents to increase once again. The state expects Colorado to add another 1.5 million people by 2050, growing to just over 7.5 million – with most of that growth focused along the Front Range.

Lakewood’s Housing Needs

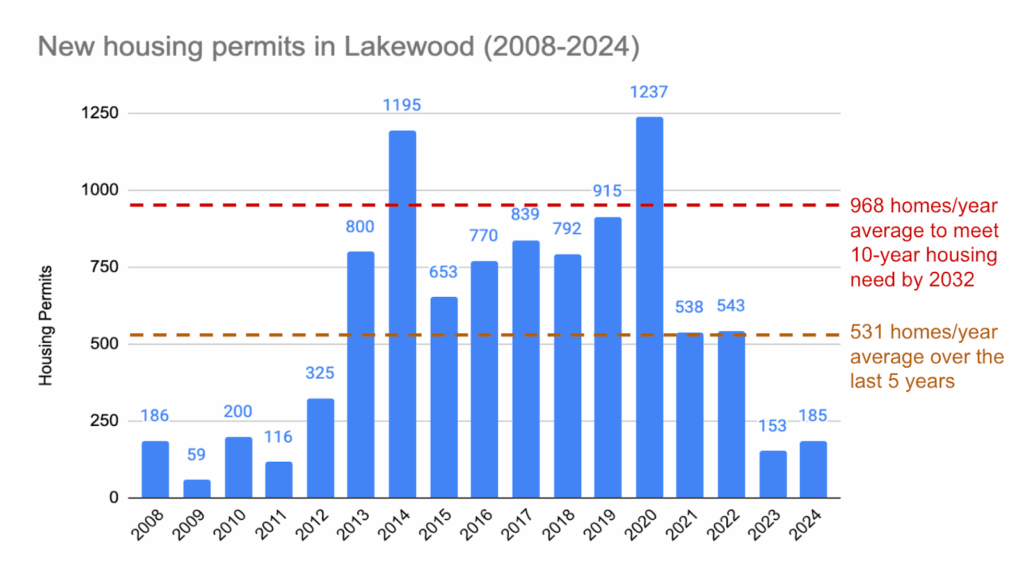

A 2024 Housing Needs Assessment from the Denver Regional Council of Governments estimates the metro area needs 216,000 new homes over the next decade – partly to address current shortages and partly to accommodate future growth. Lakewood’s share is 9,680 new homes, an average of 968 homes annually. That’s roughly 83% higher than the 5-year average of 531 new homes per year. In 2024, Lakewood permitted just 185 new homes, only a fifth of the amount needed.

Source: HUD State of the Cities Data Systems Building Permits

The drop in new home permits in 2021 can likely be attributed to Lakewood’s Strategic Growth Initiative, which set a cap for new housing production across the city. Housing markets are regional. When one city restricts housing production, it drives up housing prices in neighboring communities by forcing them to absorb that demand. To ensure that cities and towns across the state contribute to solving the regional housing affordability crisis, the Colorado State Legislature took action in 2023 to ban local anti-growth laws like Lakewood’s housing cap (House Bill 23-1255).

This chart shows that the vast majority of the housing needed in Lakewood is for households making 0-80% of the area median income. Source: Denver Regional Council of Governments Housing Needs Assessment Dashboard

What Works: Building More Housing

The good news about the housing crisis is that we know how to fix it. Research consistently points to one fundamental solution: building more homes of all types in places where people want to live. Recent studies by economists and urban planners have conclusively demonstrated that new housing construction – even market-rate housing – helps stabilize and reduce rents across metropolitan areas.

While publicly subsidized affordable housing remains essential, especially for low-income households, zoning for more modest attached and multifamily homes (rather than only large and expensive McMansions) can drive down overall housing costs with minimal public expenditure. When new housing is built, higher-income households often move in, freeing up older, more affordable units for middle- and low-income families—a process called “filtering.”

Some may question the value of adding new market-rate homes – often referred to as “luxury” – in their communities when the greatest need is for low and middle-income families. But most of us live in homes that were once considered “luxury.” Homes depreciate and filter down over time, becoming more accessible. Lakewood’s own Strategic Housing Plan notes how this process has created thousands of such naturally occurring affordable homes that are not income-restricted yet are priced at levels affordable to households earning 60-80% of the area median income (AMI).

According to one study, for every market-rate unit created in Denver, 0.82 units are made available in below-median income neighborhoods and 0.61 units are made available in the bottom 20th percentile of neighborhoods.

In addition, while the dominant assumption is that all new homes are “luxury” reserved for the ultra-wealthy, housing cost data tell a different story. Census data show that 70% of Denver apartments built between 2020 and 2023 were affordable to households making less than the area median income (100% AMI). About half of those new homes are affordable to those making less than 80% of AMI – about $82,000 per year for a 2-person household. (Affordable for these AMI levels means they spend 30% or less of their incomes on housing, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s threshold for “housing cost burden”.)

Rents for new homes built in Denver (2020-2023)

Source: American Communities Survey microdata. 2023 AMI limits for a 2-person household: $89,360/year for 80%, $111,690/year for 100% AMI, $134,040/year for 120% AMI.

That said, the private market alone cannot provide housing for those earning under 30% of AMI. Meeting the need requires greater public subsidies to produce and preserve more deed-restricted affordable housing. State and local governments have implemented numerous strategies to deliver and incentivize more affordable housing, including through Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC), Inclusionary Zoning, Proposition 123 funds, Community Land Trusts, density and height bonuses, and other creative policy tools.

More housing in urban areas is good for the environment

Pro-housing policies present an opportunity to not only address the high cost of housing, but to also build more climate-friendly, water-wise, and transportation-efficient communities. Restricting new housing in urban areas doesn’t erase demand, but it does fuel exurban sprawl, pushing growth far from jobs, transit, and services. According to a study from the Colorado Energy Office, under current policies, nearly half of the new housing development Colorado expects by 2050 will come in the form of exurban sprawl on open space and agricultural land, in areas at higher risk of ever-worsening climate disasters like Boulder County’s 2021 Marshall Fire. Over the last 25 years, exurban sprawl has nearly doubled the size of the Denver metro’s projected growth area from 700 square miles to 1,308 square miles, resulting in massive habitat loss for wildlife.

A scenario where we instead focus growth in already-developed areas would reduce sprawl while also cutting total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the new housing by 31% – even without energy code updates and other sustainable building policies. That’s because attached and multifamily housing types are inherently more energy efficient. On average, they use 30–55% less energy and 63–86% less water than single-detached homes, mostly because shared walls make them easier and cheaper to heat and cool.

Transportation is Colorado’s largest source of GHG emissions and the sector furthest from meeting our 2030 climate targets. While electric vehicles are critical, they are insufficient on their own – so we must also look for ways to reduce vehicle travel. When people can live near their work, school, and other daily needs, it becomes much easier to walk, bike, or take public transit to get around. And even when people do need to drive, distances to their destinations tend to be shorter, causing less pollution. Colorado households in compact, mixed-use areas drive 20–40% less and own fewer cars. This not only cuts pollution, but it also saves Coloradans money on transportation – the second-highest household expense after housing.

An analysis by the City of Denver found that residents in low-density neighborhoods produce more than twice the carbon emissions and use 75% more water compared to those living in more compact and urban neighborhoods, as illustrated in the table below.

Source: Land Development Category Comparison

(Typical Household in City of Denver, 2015 – from Blueprint Denver)

Key reforms to create more housing choices in Lakewood

Luckily, Lakewood is currently considering a package of reforms to address its housing affordability crisis. First, the City is on the verge of adopting a new Comprehensive Plan that calls for more housing choices and affordable housing, which research shows will reduce homelessness. The Plan also highlights transportation goals to create more walkable and transit-friendly communities by locating more homes near jobs and public transit.

Second, Lakewood is developing a zoning code update to allow smaller and more affordable starter homes in neighborhoods currently limited to single detached units. “Middle housing” types such as duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, and townhomes are generally more affordable than stand-alone single-family homes. This is partly because they allow for more housing units on the same amount of land, which is a major factor in construction costs. These lower-cost options expand homeownership opportunities and offer renters options outside of large apartment blocks, which currently make up a majority of rental housing.

Lastly, in response to a package of 2024 state land use laws, Lakewood is considering a set of reforms to encourage more housing near transit (HB24-1313), eliminate costly and excessive parking mandates (HB24-1304), and legalize Accessory Dwelling Units (HB24-1152). Lakewood’s existing land use code and proposed Comprehensive Plan align with these state laws.

These reforms, among others, can put Lakewood on track to meet its housing goals. In the process, Lakewood can build a community that’s more affordable and accessible to all.